In this installment of '10 questions with ...' we chat with Dr Fiona McCormack about her latest book, Private Oceans: The Enclosure and Marketisation of the Seas (2017), which was launched as part of an ASAA/NZ event at the 2017 Shifting States conference in Adelaide.

1. How would you describe your book to a non-anthropological audience?

While the book is centred on fisheries, it is really a story about how a relatively recent and increasingly dominant regime for managing the relationship between people and fish can have radical and disruptive social consequences. In this sense, Individual Transferable Quota systems (ITQs) are a kind of blue print for a whole suite of new environmental managment tools, often called market-based instruments or payment for ecosystem services. These are rooted in the supposed superiority of private property rights, in the ‘market’ as the optimal determiner of distribution rights, and in the idea that sustainable outcomes will naturally follow. The book breaks down each aspect of this argument and shows how this thinking is ultimately tied to a particular political and economic model which works to undermine local and indigenous knowledge, small-scale livelihoods and ways of life, though also sustainability.

Yet, the book also details everyday forms of resistance as well as more exceptional examples. I draw on fieldwork from Aotearoa, Ireland, Hawaii and Iceland to show how ITQ regimes hit against local cultures, histories and economies, becoming altered by this engagement. In Aotearoa, for example, ITQs are bound up with an historic struggle for fishing rights, a hard-won pan-Māori settlement and current attempts to work through the contradictions wrought by a management system in which value is assigned to quota trading rather than fishing. On the gaeltacht (Irish speaking) island of Árainn Mhór, where historically diverse catches have been reduced to a singular non-quota species (brown crab), islanders are gaining traction in their arguments for recognition of indigenous rights and their island home as a European recognised heritage site. In Iceland, ITQs tell a fantastical tale of corruption and financialisation, are key to understanding the spectacular financial crash of 2008 and, following a sustained local critique from small-scale fishers, exemplify how even enclosures can be (albeit minimally) reversed.

2. Why now?

Aotearoa is celebrated as the site were ITQs where first introduced and where the most comprehensive regime exists, covering virtually all commercial fish stock. Currently, some form of ITQs are being rolled out in many of the world’s fisheries. Globally, a growing number of anthropologists and marine social scientists are engaging with this topic. The book is a timely intervention in the debate.

3. What kind of assumptions do you unsettle in this book?

Hopefully many! First, that fishing in an ITQ regime is not primarily about catching fish in the sea, but rather about quota trading or the generation of virtual fish. Second, that way that ‘sustainability’ is conceived in ITQ fisheries is not geared towards sustaining the life cycle of fish in the sea, but protecting and enhancing the rights of ITQ holders. Third, the free and equitable market promised by neoliberal entrepreneurs has emerged, in this instance, as a kind of feudal system. Icelandic fishers, for instance, clearly articulate a distinction between “sea lords” (large consolidated quota companies) and “serfs” (quota leasing fishers). And rather than a “rolling back of the state”, in ITQ fisheries there is an increasing need for central government to address sustainability and social equity issues; for example, dumping and discarding of catch and the consolidation of quota rights. Fourth, the settlement of Māori claims to fisheries in the context of an ITQ regime has not enabled Māori iwi to “get into the business of fishing”, at least in terms of actual production.

4. What drew you to your topic?

I wanted to tell a story of human-environment relations and how these have been compromised by the introduction of a system rooted in an extremely neoliberal understanding of both humans and the environment. I also wanted to highlight the importance of the seascape for coastal and island peoples, and of their struggles to maintain cultural traditions, identity and livelihoods. I have a longstanding interest in exploring the inequities that result from colonisation and continue to impact on the lives of indigenous people. My doctoral research was on Māori fisheries, a crucial Treaty of Waitangi issue at the time. I subsequently became interested in comparative work on ITQ regimes, and Hawaii as a site where ITQs have, to date, not been introduced.

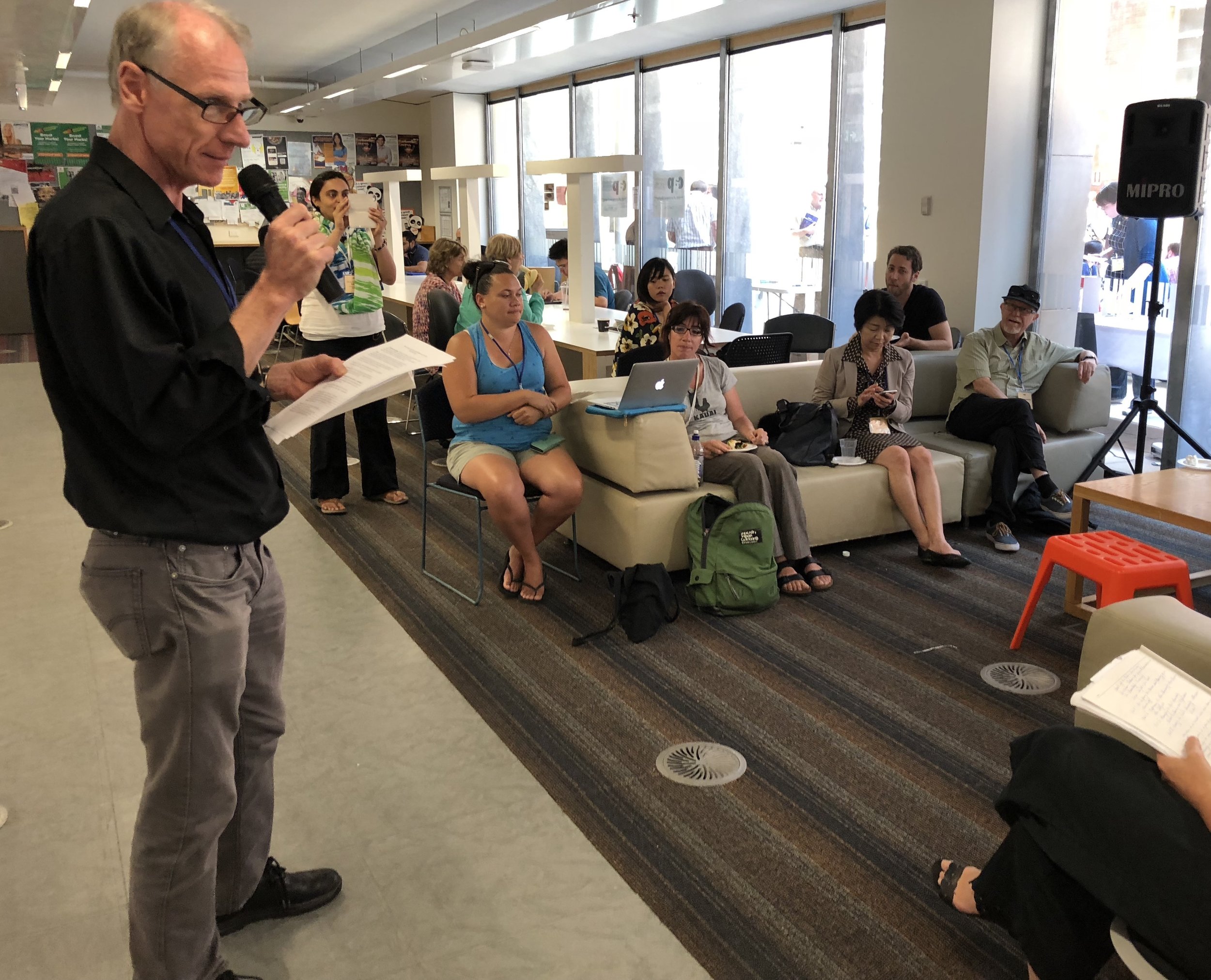

Professor Cris Shore introduces Dr Fiona McCormack's book Private Oceans at the ASAA/NZ book launch in Adelaide, November 2017. Photo: Caroline Bennett

5. How was your publisher?

Brilliant, though the book proposal stage was very tense. My proposal was peer reviewed by three experts, revised, and reviewed again. It took about four months before I got a contract. Pluto was really supportive during the writing, editing and proofing process. Everyone I dealt with was friendly, professional and often funny.

6. What’s your favourite part of the book?

I don’t know if I really have one. I like the second chapter where I explore the dark side of ‘sustainability’ and engage with the actual science involved in determining commercial fishing levels, the fourth which looks at gift economies in Hawaii and the fifth where I use precarity and nostaligia to understand fisheries in Donegal, Ireland.

7. What have you learnt about yourself as a writer as a result of this?

I love writing and take great pleasure from crafting sentences. I do need to be careful of making up words which, while I am convinced they already exist, cannot be found in any dictionary.

8. Would you write another book?

Absolutely.

9. What’s next?

I have a research project that I am working on this year looking at how iwi settlement quota is operationalised and exploring the reasons why most iwi lease rather than fish their quota. I am researching notions of financialisation, kaitiakitanga, sustainability, hope, post-treaty settlement Māori society and the ocean as a new frontier. I am also trying to conceptualise a project on housing, homes/homelessness and the supposed sharing economy of Airbnb type ventures.

10. What are you reading at the moment?

Becoming Salmon by Marianne Lien.

Dr Fiona McCormack is a senior lecturer in anthropology at the University of Waikato.